How Hiroshi Yoshida’s Journey to India in 1930 Transformed Japanese Art and Gave the World a New Lens on the East

When a Japanese artist travels to India

The caption almost sounds like a simple meme, but behind it lies a true and remarkable story. In 1930, Hiroshi Yoshida, one of Japan’s greatest painters and woodblock print artists, left his homeland to explore India. What he found in Delhi, Agra, Jaipur, Varanasi, and Madurai wasn’t just exotic scenery to take home as souvenirs—it was inspiration that would transform his art and add a new chapter to cultural exchange between two of Asia’s oldest civilizations.

Yoshida, already celebrated in Japan for blending traditional woodblock methods with Western-style realism, believed in painting what he saw with his own eyes. That’s why his four-month journey across India mattered so much. He didn’t just copy photographs or rely on secondhand descriptions—he walked the streets, sketched by temples, stood before monuments, and watched the light change hour by hour. India, with its architecture, its rituals, and its deep, dazzling colors, became part of his artistic DNA.

The story of Hiroshi Yoshida begins decades before his India travels. Born in 1876, he became part of the shin-hanga (“new prints”) movement, which sought to modernize the centuries-old Japanese woodblock tradition. While ukiyo-e masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige had immortalized Japanese landscapes in the Edo period, Yoshida brought something new—he fused those techniques with Western perspective, realism, and shading. His art looked familiar and yet strikingly modern, a reason he gained international fame.

By the time he boarded a ship for India, Yoshida had already traveled to America and Europe, painting the Grand Canyon, the Alps, and even the canals of Venice. But India was different. India wasn’t just geography—it was history, religion, and myth, alive in every stone.

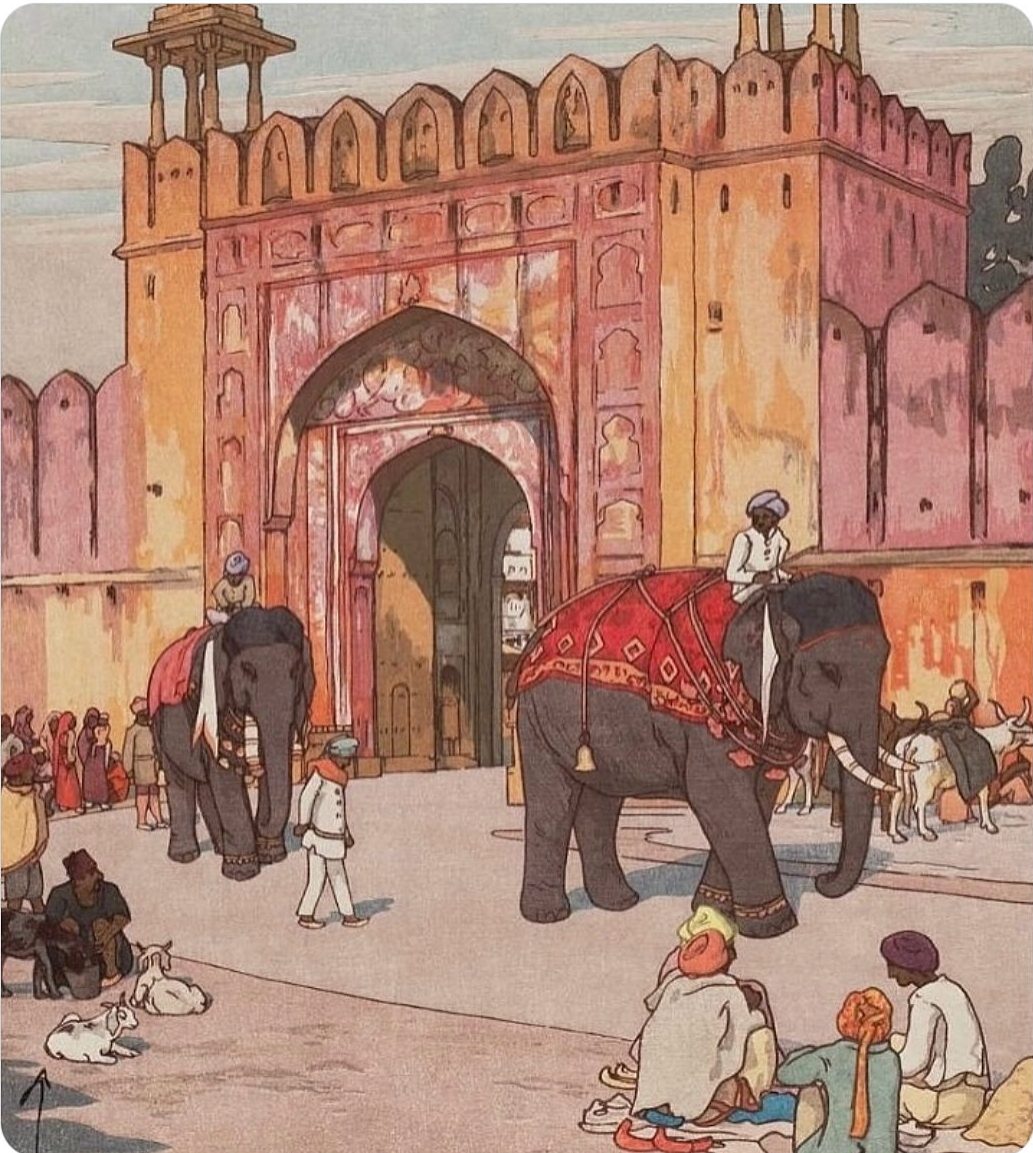

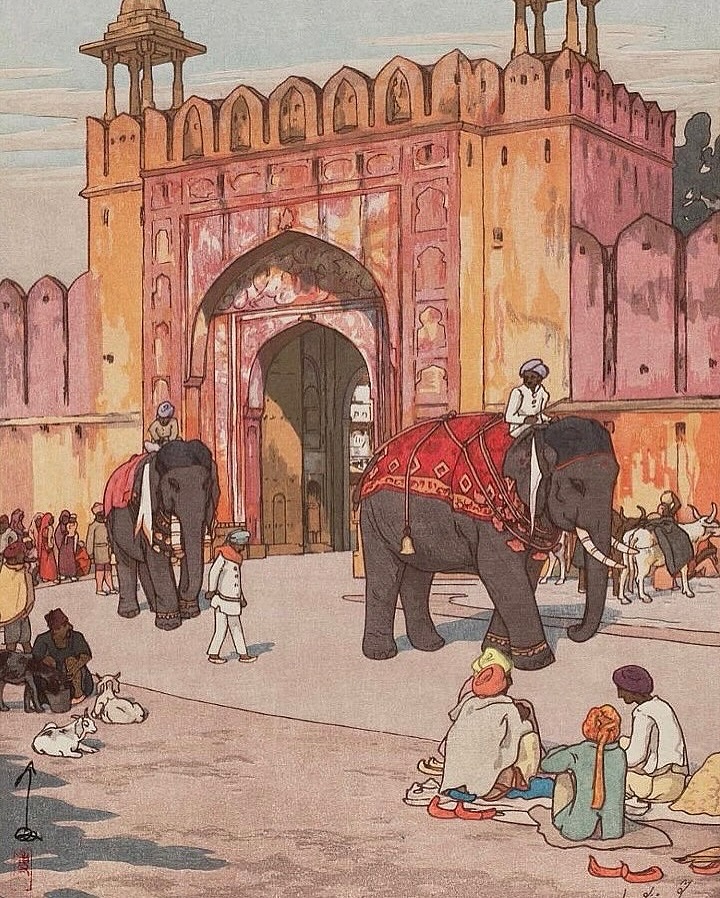

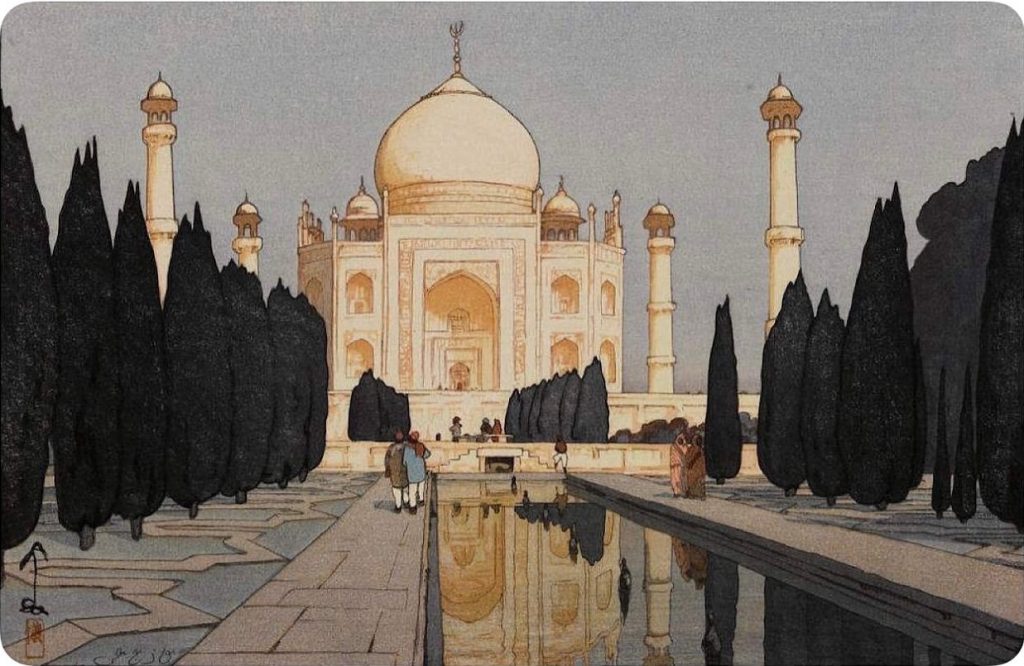

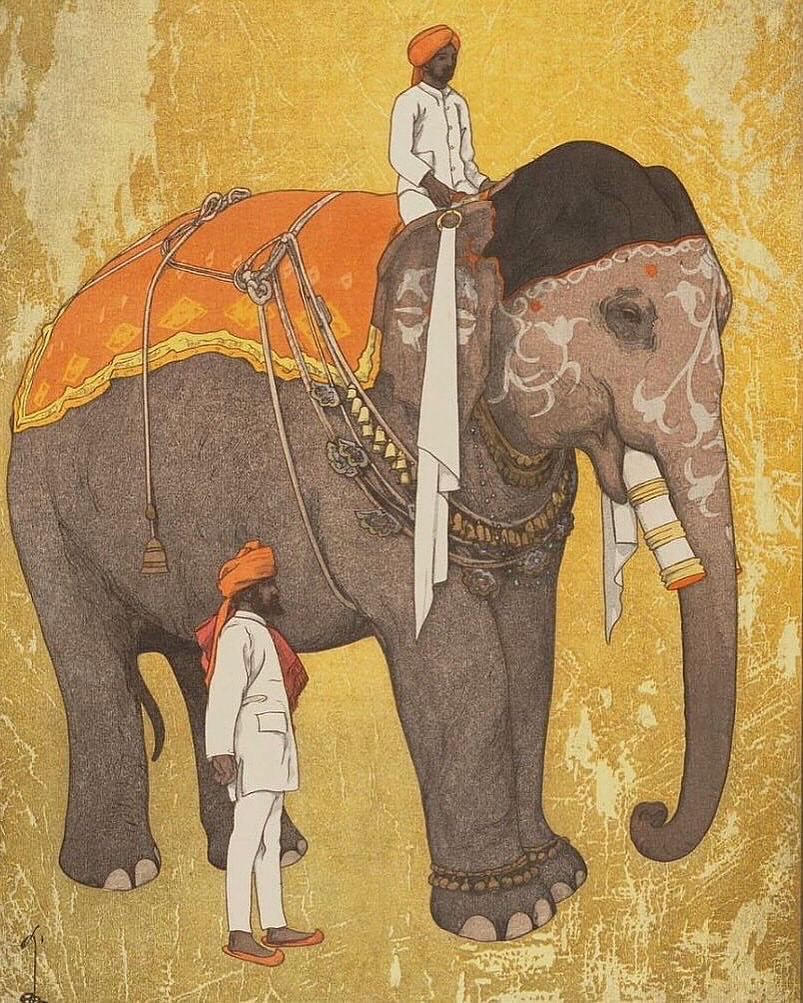

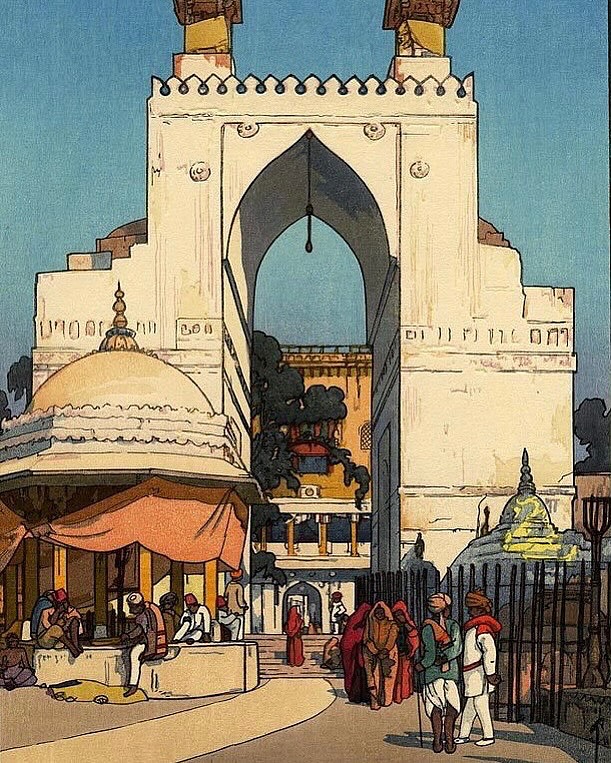

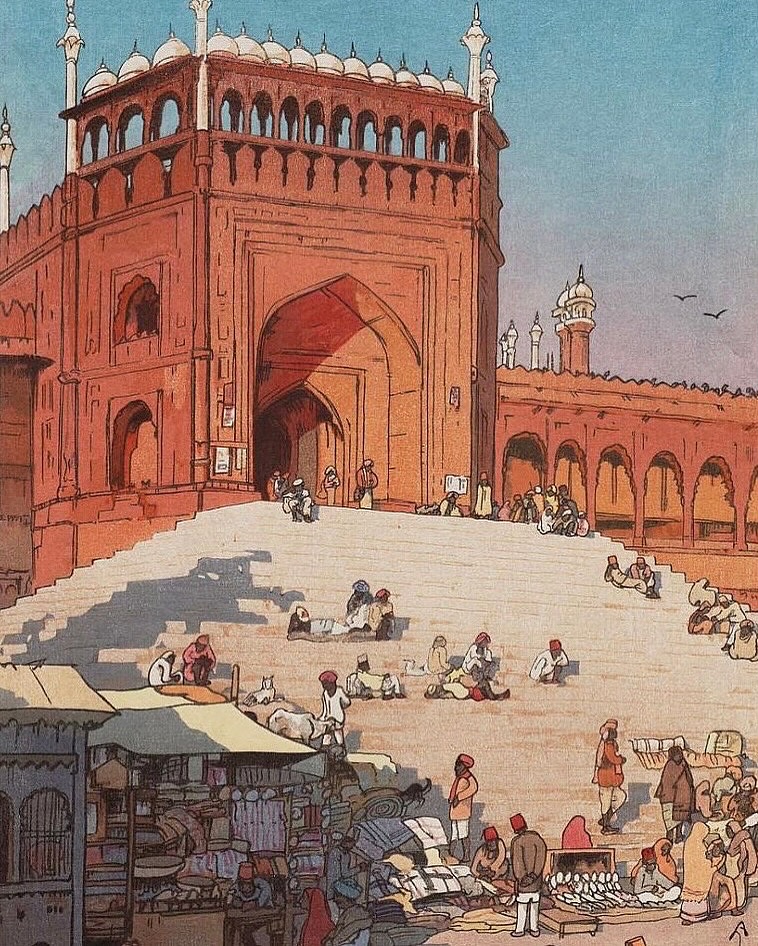

In Delhi, he stood before the Red Fort, its massive sandstone walls glowing under the winter sun. In Agra, he was captivated by the Taj Mahal, a monument that shifted from ivory to pink to gold depending on the time of day. In Jaipur, he found himself sketching elephants decorated in cloth and jewelry, walking beneath pink city gates that looked like something out of a dream.

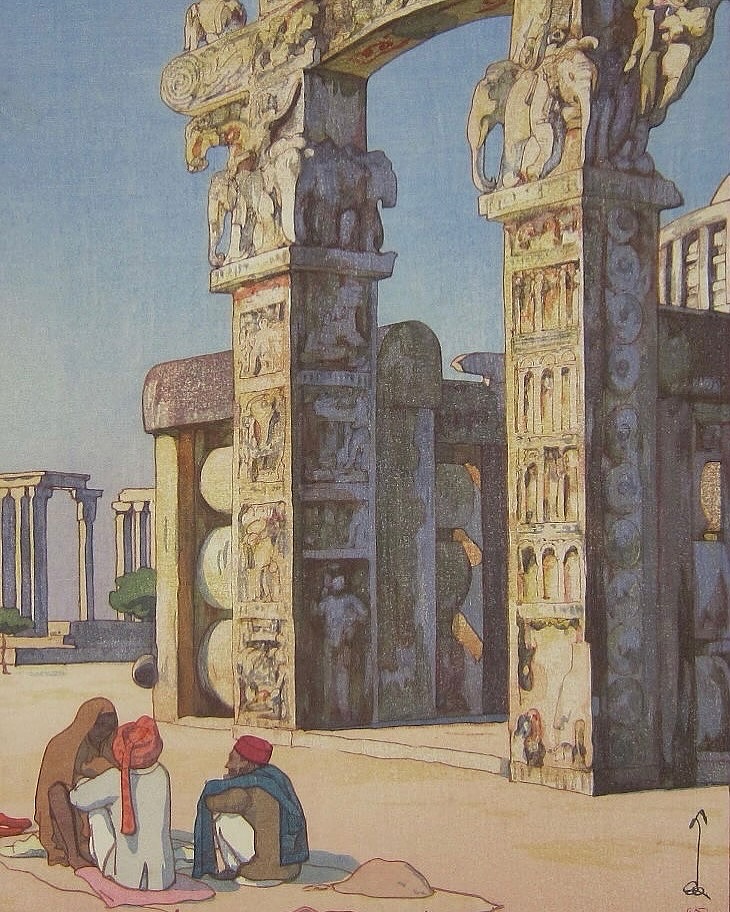

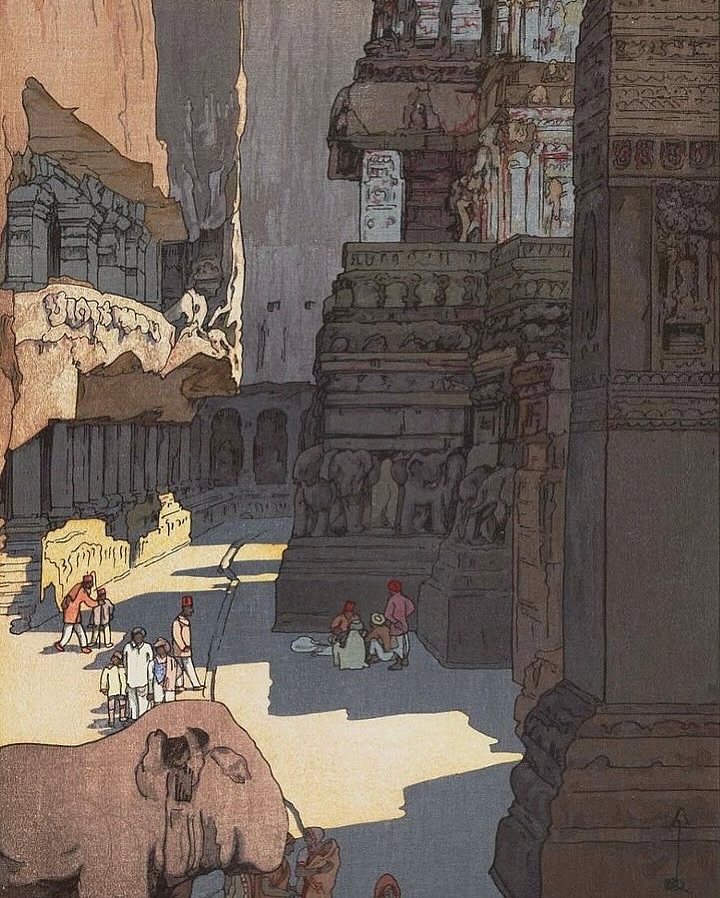

Varanasi was perhaps the most overwhelming of all. The sacred Ganges flowed past endless ghats where pilgrims bathed, prayed, and sent offerings floating downstream. For Yoshida, used to the quiet order of Japanese landscapes, this was a new kind of beauty—loud, crowded, messy, but profoundly spiritual. And when he finally reached Madurai in South India, the towering Meenakshi Temple left him speechless. Its colorful sculptures of gods, demons, and celestial beings felt like a world carved in stone.

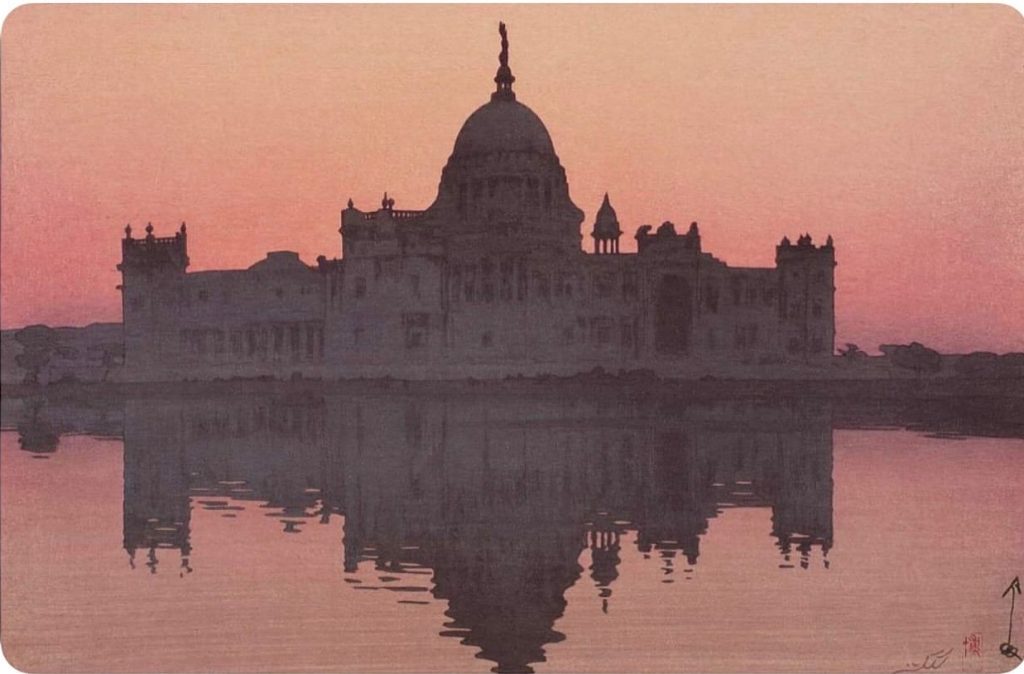

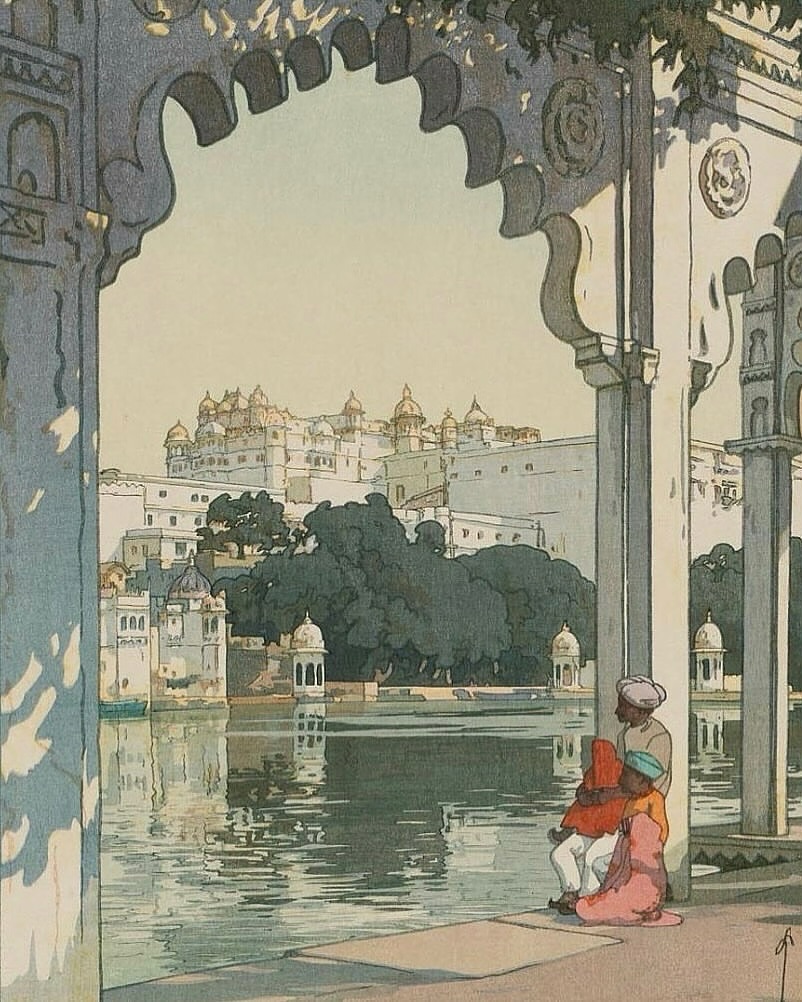

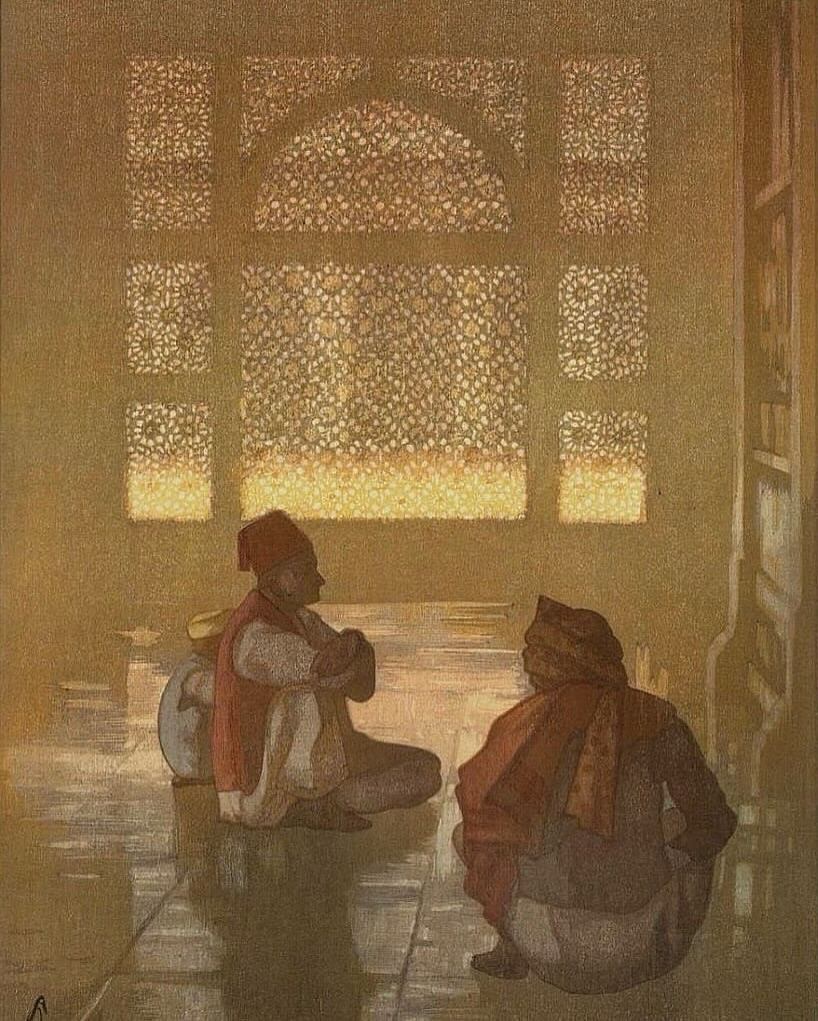

Back in Japan, Yoshida transformed these sketches into prints. He worked carefully, combining the traditional multi-block woodcut technique with his painter’s eye for detail. The result was extraordinary. His India prints didn’t feel like copies or postcards—they carried atmosphere. You could almost hear the footsteps in an Agra courtyard, feel the heat of a Jaipur afternoon, or imagine the chanting along the Ganges at dawn.

What made them unique was how they blended Japanese and Indian sensibilities. Yoshida used delicate shading, muted tones, and fine outlines typical of Japanese aesthetics, but he applied them to subjects overflowing with Indian grandeur. Elephants, domes, palaces, and temples filled his frames, yet they retained a quiet elegance that was distinctly Japanese. It was as if two traditions were shaking hands on paper.

Traveling with him was his teenage son, Tōshi Yoshida. For the boy, this trip was life-changing. He absorbed his father’s lessons not just in art but in curiosity, respect, and humility toward other cultures. Tōshi would later grow into an acclaimed artist himself, carrying forward the Yoshida family legacy. India, in many ways, shaped two generations of artists at once.

Nearly a century later, these prints remain treasured works of art. They are displayed in museums and collected worldwide, not only for their beauty but for what they represent: cultural exchange at its most genuine. Yoshida didn’t come to India to impose his vision—he came to listen, to see, and to learn. And then he carried those impressions home, sharing them with audiences who might never set foot on Indian soil.

There is also something poetic about the journey. Japan and India had been connected for centuries through Buddhism, which spread eastward from India to China, Korea, and finally Japan. Yoshida’s travels felt like a circle completing itself—an artist from Japan returning to the land that once sent spiritual ideas that shaped his own culture. His prints, therefore, aren’t just travel art—they are a conversation across time and tradition.

In today’s world of easy flights and instant photos, it’s hard to imagine how ambitious Yoshida’s journey was in 1930. Travel was slow, uncertain, and demanding. Yet he endured it because he believed art had to be rooted in real experience. That philosophy shines through his India series. Every stroke reflects the patience of a man who sat before his subject and let it sink into his heart before putting it onto paper.

His works remind us why travel matters. It isn’t about collecting souvenirs—it’s about being changed by what we see. Yoshida returned to Japan not just with sketches but with a deeper understanding of beauty, one that expanded his art and, through it, touched the world.

When we look at his prints today, we see more than India or Japan. We see the shared human desire to connect through beauty. We see how one man’s journey almost a century ago still speaks to us in an age of digital images and shrinking distances. And most of all, we see proof that art, when created with respect and love, becomes a bridge that never breaks.

Daniel Reed is a curious mind with a passion for breaking down how the world works. With a background in mechanical engineering and digital media, he turns complex ideas into easy-to-understand articles that entertain and inform. From vintage tools and modern tech to viral internet debates and life hacks, Daniel is always on the hunt for the “why” behind the everyday. His goal is simple: make learning feel like scrolling through your favorite feed — addictive, surprising, and fun.