Photographer Katja Kemnitz’s Series “Too Much Love” Shows Why Worn-Out Toys Mean More Than Perfect Ones

There’s something magical about the way children love their toys. It’s not the kind of love that depends on how flawless the toy looks or how much it costs. Instead, it’s the kind of love that transforms a simple object into a lifelong friend. A stuffed rabbit missing an ear, a teddy bear with worn fur, a doll whose once-bright dress is now faded—these are not just toys. For a child, they are companions, guardians of secrets, and silent witnesses to growing up.

Photographer Katja Kemnitz captured this beautifully in her moving series “Too Much Love.” The idea came from her own experience as a mother. Her daughter once had a plush dog that she carried everywhere. It slept beside her, traveled with her, comforted her when she was sad, and cheered her when she was happy. Over time, the toy grew worn, its fur matted and its stuffing uneven. But to her daughter, it became more precious with every scar of love.

Years later, Kemnitz came across the exact same toy in a shop. It was pristine, fluffy, and perfect, untouched by the messy love of a child. Naturally, she thought her daughter would be thrilled. But the reaction was the opposite. The child barely looked at the new one, her heart firmly attached to the old, worn friend she had carried for years. That moment planted the seed for “Too Much Love.”

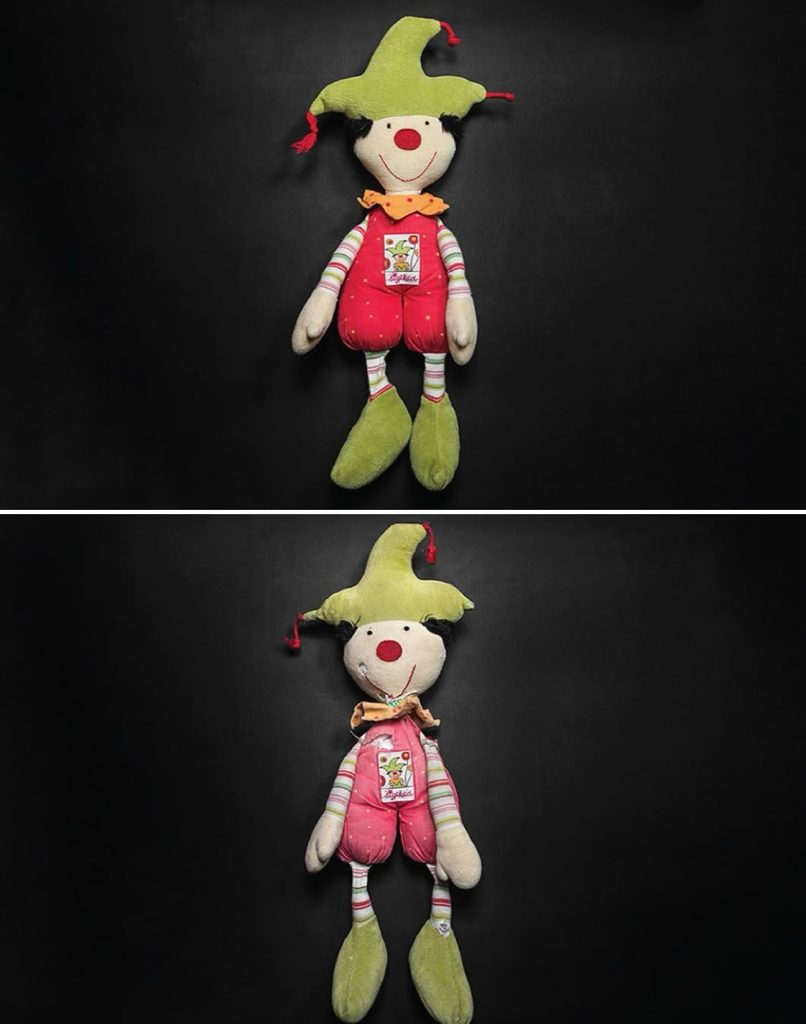

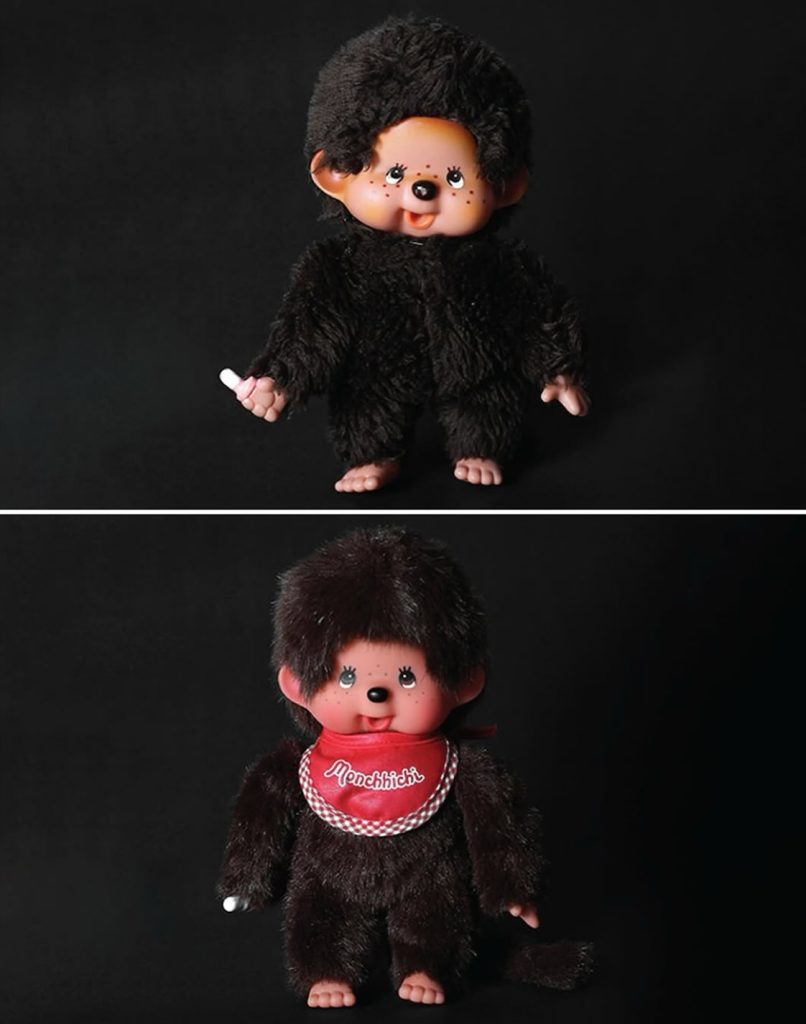

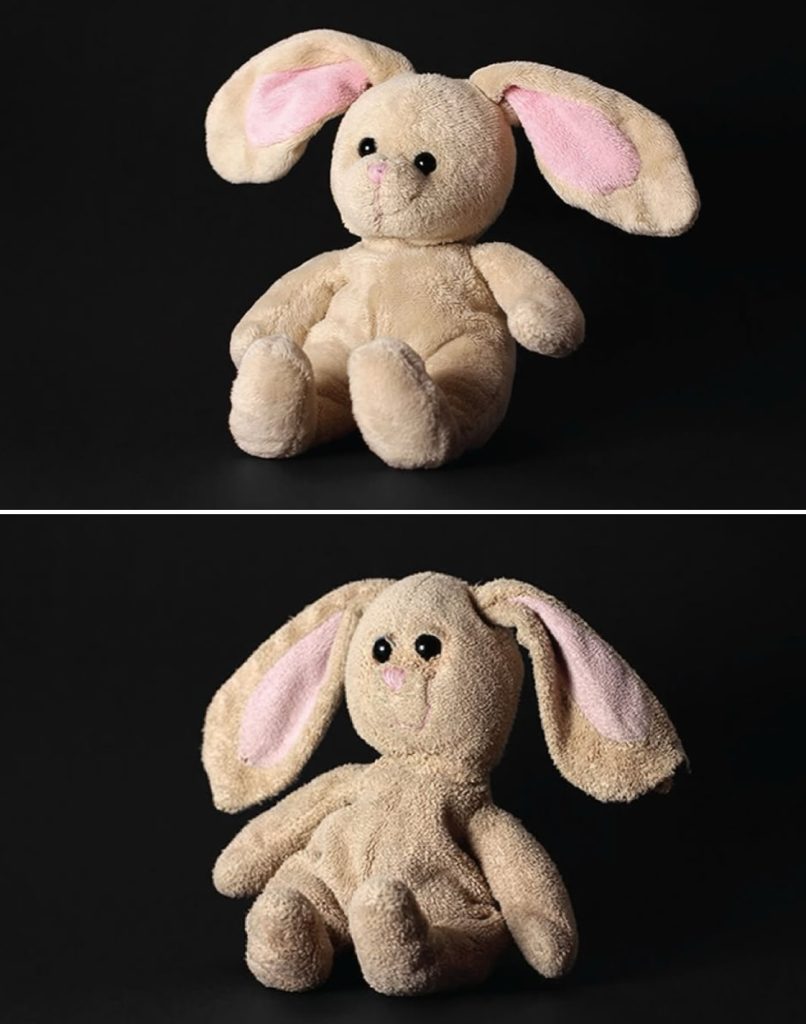

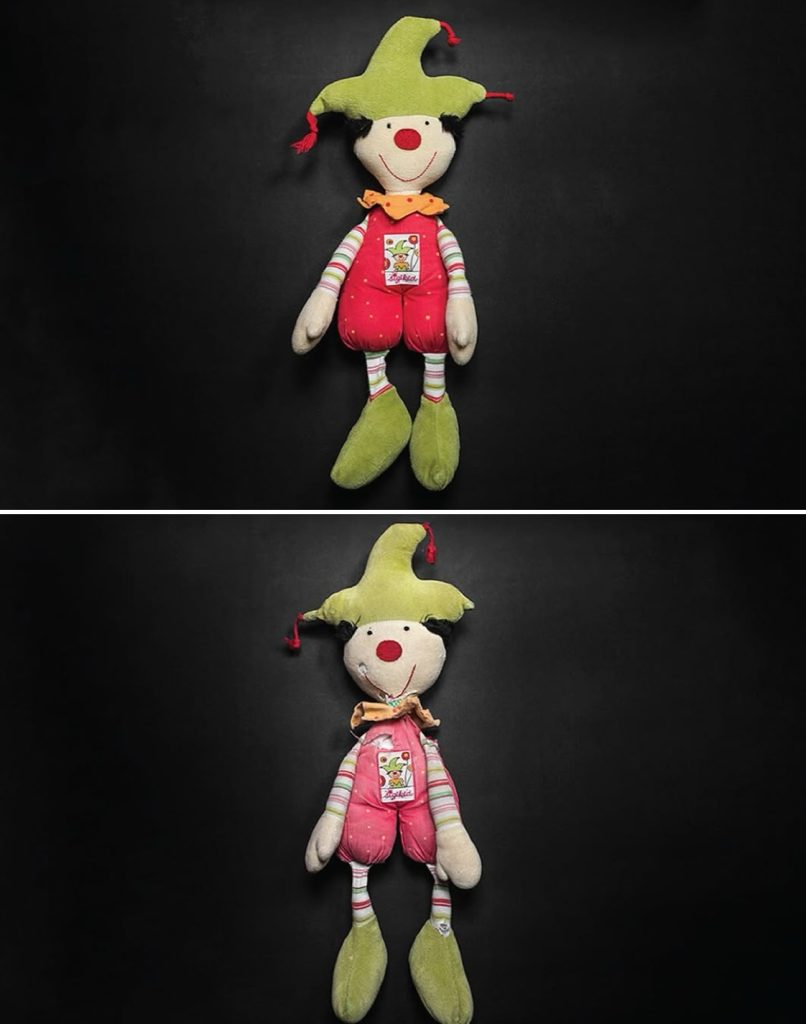

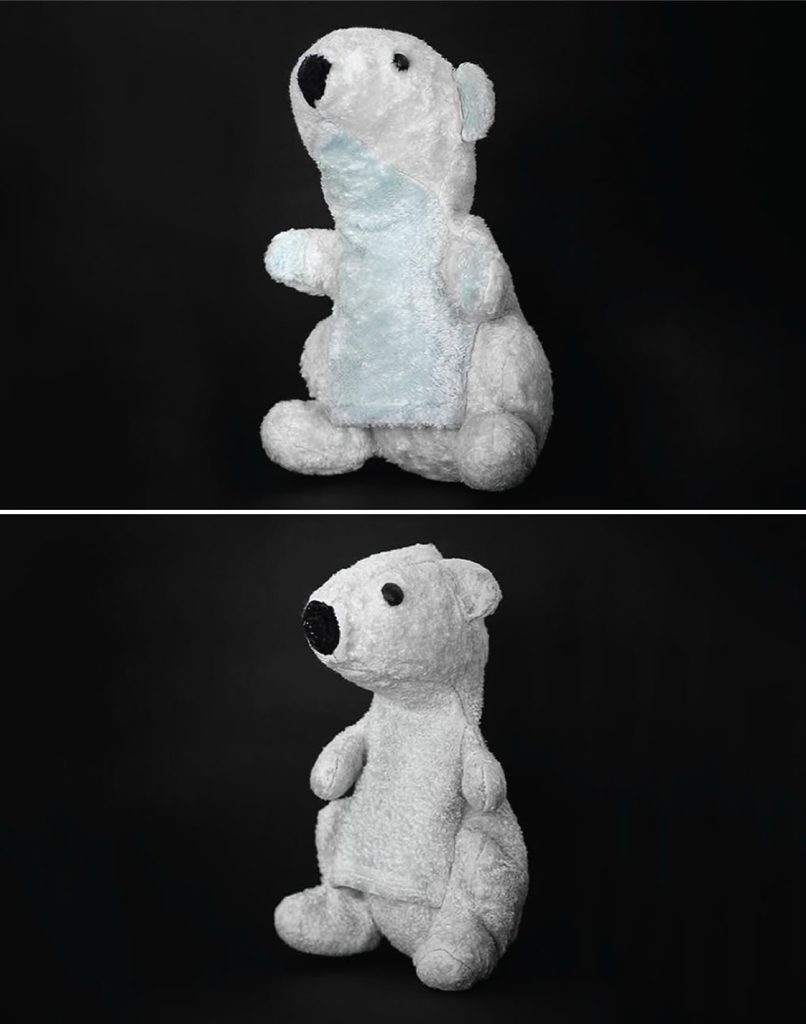

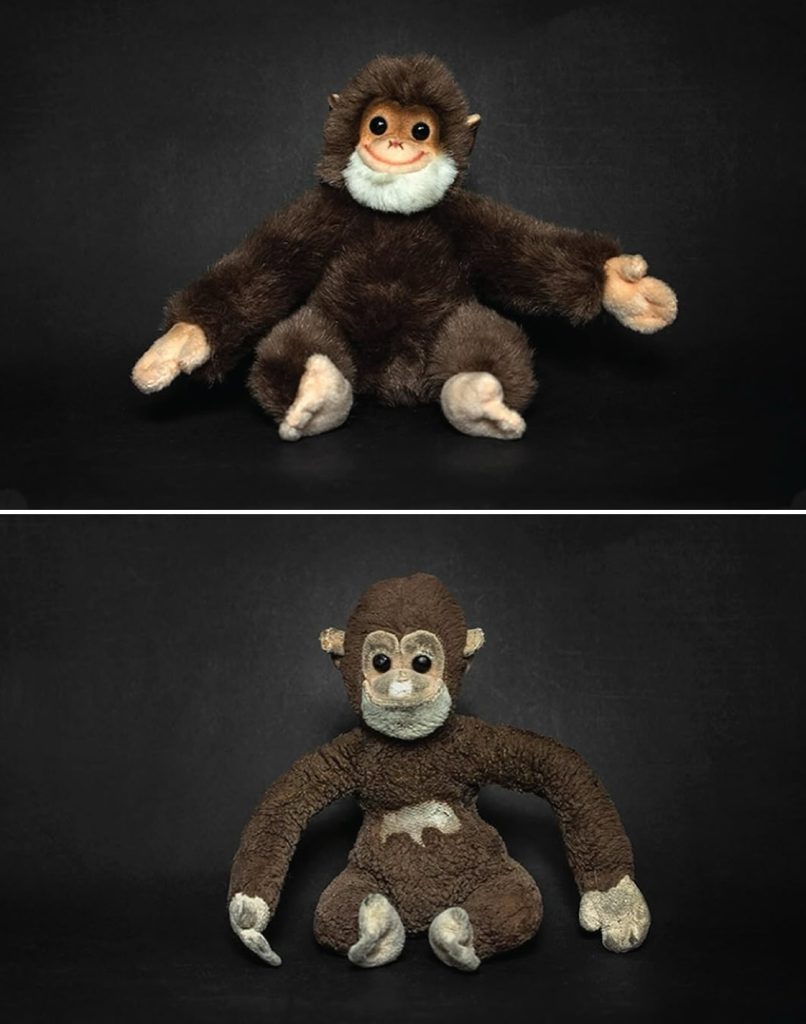

Kemnitz began photographing beloved toys beside their untouched twins. The result is striking. On one side, you see a toy as it was meant to be—bright, flawless, untouched. On the other, you see the version shaped by years of love. Faded fur, flattened limbs, missing parts, yet brimming with meaning. The worn versions tell stories the new ones never could. They are a record of hugs, of tears wiped away, of journeys carried in small hands.

What makes the project so powerful is its universal resonance. Everyone has had something like this—a toy, a blanket, a piece of clothing—that carried meaning far beyond its physical form. Maybe it was a teddy bear that went with you on every sleepover. Maybe it was a doll that you whispered secrets to. Maybe it was a soft blanket that comforted you during storms. Over time, these things become part of who we are.

When you look at the photos in Kemnitz’s series, it’s impossible not to feel a tug of nostalgia. The pristine toys look beautiful, yes. But the worn ones feel alive. They carry an invisible history, one that belongs to the child who loved them. And isn’t that the essence of love itself? It leaves marks. It changes things. It softens edges, wears down surfaces, and sometimes breaks things apart. But in that process, it creates something infinitely more meaningful than perfection.

The series is also a quiet reminder about the value of imperfection. We live in a world that often worships newness, shininess, and flawlessness. Ads tell us to replace the old with the new. Social media shows us curated, polished lives. But “Too Much Love” argues the opposite—that true beauty often lies in what has been worn, touched, and changed by time. The toys that children treasure are meaningful not despite their imperfections, but because of them.

This lesson extends beyond toys. Relationships, too, are made precious not by how perfect they look but by how deeply they are lived in. Families, friendships, even the love between parents and children—these bonds grow stronger through the struggles, the wear and tear, the messy, imperfect moments. Just like a threadbare toy, they carry the imprints of time, and those imprints make them real.

Kemnitz’s work has touched people far beyond the photography world. Many parents who see her images are reminded of their own children’s beloved toys. Some recall the heartbreak of having to secretly replace or repair them. Others confess they’ve kept their grown children’s old stuffed animals in boxes, unable to throw away something that holds so much memory. For adults without children, the series still resonates—it reminds us of our own childhoods, and the objects that meant the world to us back then.

It also raises fascinating questions about memory and attachment. Why do we hold onto certain objects? Why do some things become part of our identity while others fade into the background? Psychologists often say it’s because objects can anchor memories. A worn toy is not just fabric and stuffing—it’s a container for a thousand childhood moments. That’s why the pristine twin, no matter how flawless, feels empty. It hasn’t lived those moments.

When you look at the side-by-side photographs, it’s easy to see the difference. The new toy looks like a product. The old one looks like a friend. You can imagine the nights it spent under the covers, the trips it took stuffed into backpacks, the times it was held tightly when the world felt scary. Its imperfections are not flaws—they’re evidence of love.

“Too Much Love” is more than just a photography project. It’s a meditation on what really gives life meaning. It’s not perfection, not shininess, not the untouched beauty of something new. It’s the marks left by time and by love. It’s the wear and tear that comes from being needed, from being part of someone’s story.

As adults, we often forget this. We chase after perfection, trying to keep our lives tidy and unblemished. But maybe the real treasures are the things that have been through it all with us. The things that look worn but feel alive. Kemnitz reminds us that imperfection can be more beautiful, more valuable, and more human than perfection ever could.

Looking at her series, you can’t help but think of the things you’ve loved too much. Maybe they’re still with you, tucked in a box or hidden on a shelf. Maybe they’ve been lost along the way. But the truth remains: love changes things, and that change is what makes them irreplaceable.

Daniel Reed is a curious mind with a passion for breaking down how the world works. With a background in mechanical engineering and digital media, he turns complex ideas into easy-to-understand articles that entertain and inform. From vintage tools and modern tech to viral internet debates and life hacks, Daniel is always on the hunt for the “why” behind the everyday. His goal is simple: make learning feel like scrolling through your favorite feed — addictive, surprising, and fun.