How Elizabeth Keith, a Scottish Traveler, Captured the Soul of Asia Through Woodblock Prints and Stories

There are some lives that never go as planned, and maybe that’s where their beauty lies. Elizabeth Keith was born in Scotland in 1887, with no early indication that she would one day become one of the few Western artists to embrace and honor East Asian culture in such a lasting way. When she boarded a ship to Japan in 1915, she thought she was only going for a brief visit to see her sister and brother-in-law. What awaited her instead was a turning point that transformed her life, her art, and her legacy.

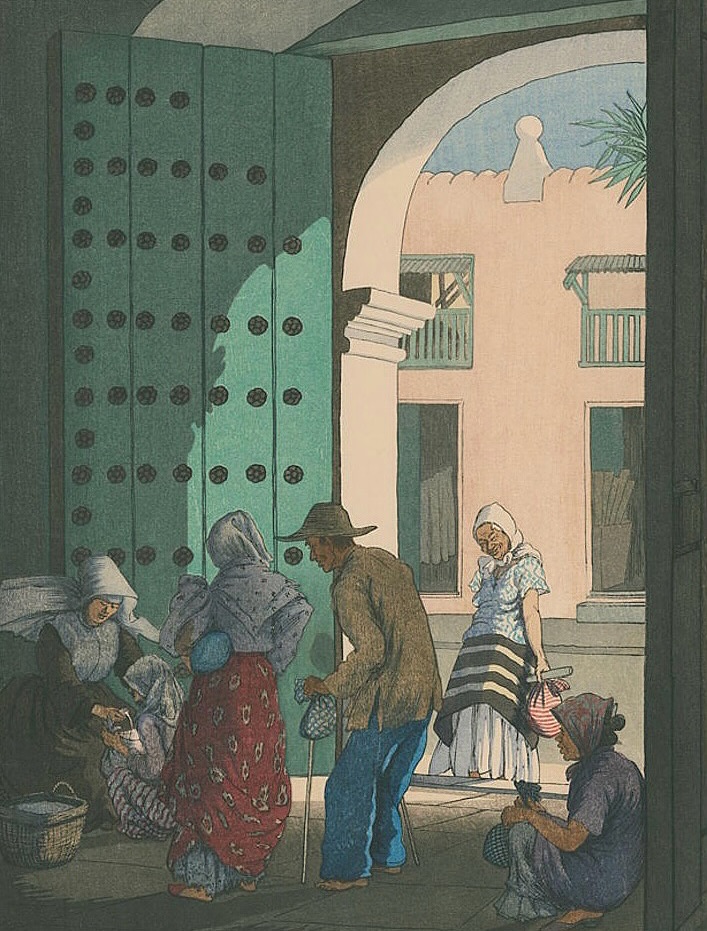

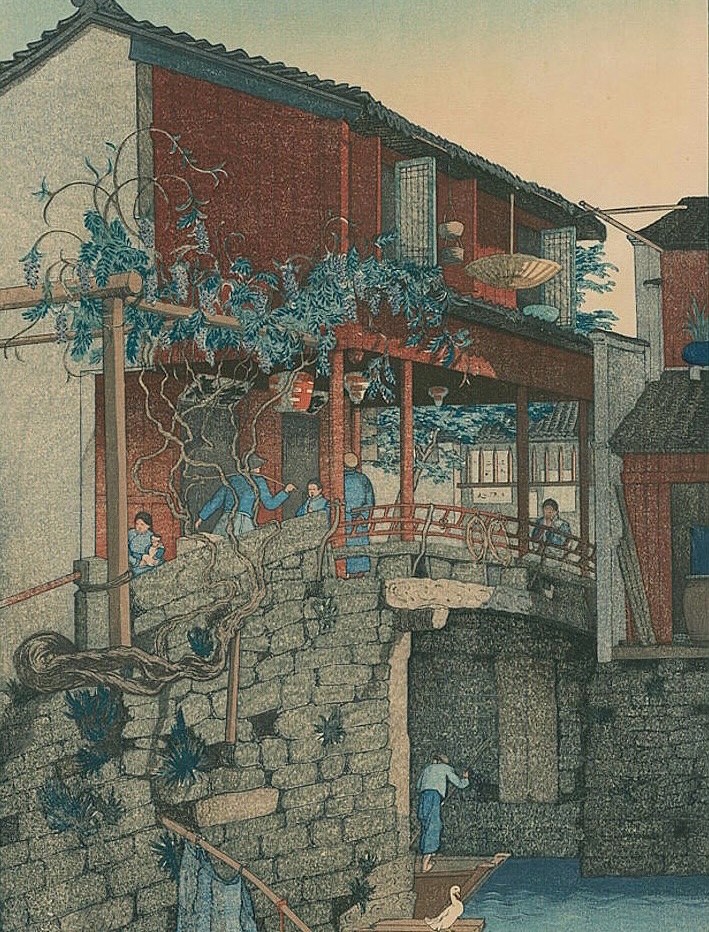

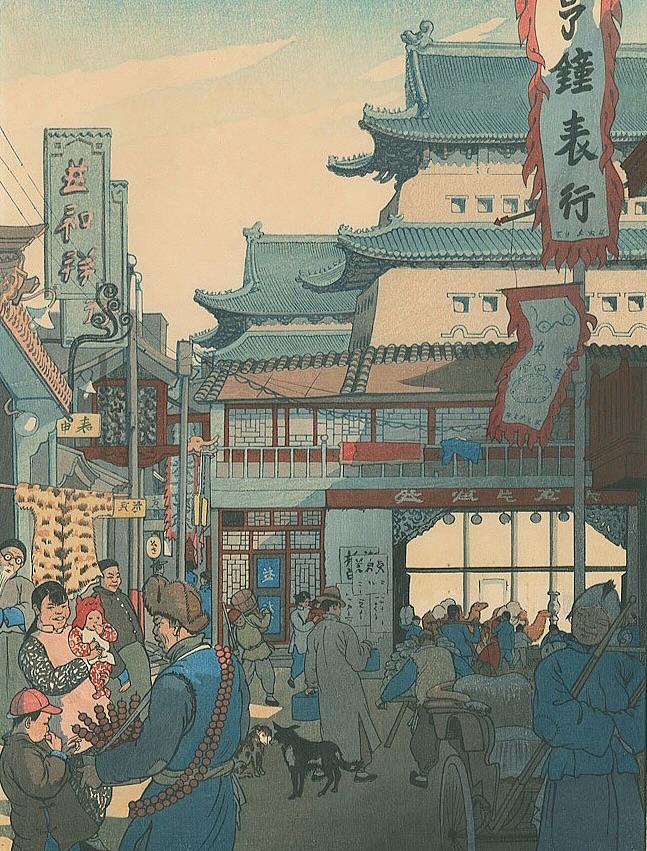

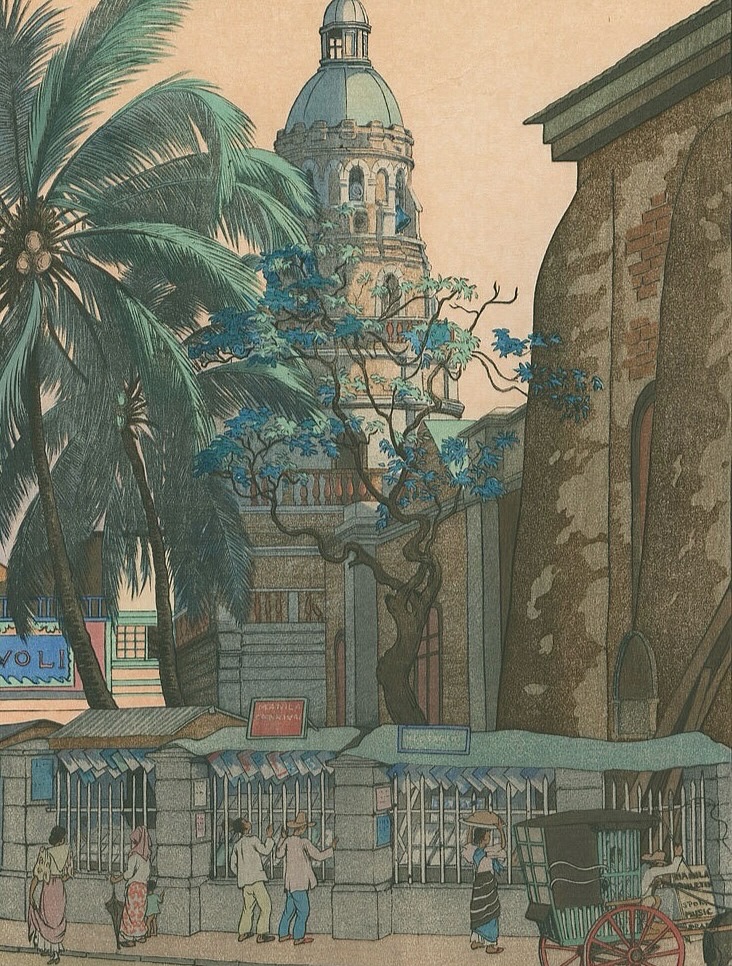

Japan, with its quiet gardens, patterned fabrics, and delicate light, overwhelmed her senses. At first, she did what came naturally: she sketched. She painted watercolors of what she saw, trying to capture not just the scenery but the feeling of being immersed in another world. The trip that was supposed to be short stretched into years of wandering. She went not only through Japan, but also Korea, China, and the Philippines. Each journey deepened her fascination and gave her a new language to explore—the language of color, shadow, and line.

Keith’s turning point came when she met Watanabe Shōzaburō, the Japanese publisher who had helped revive the traditional art of woodblock printing. He encouraged her to turn her sketches into prints using the shin-hanga style, a modern version of an ancient craft. Learning this wasn’t simple—it required patience, respect for tradition, and collaboration with master carvers and printers. But Elizabeth Keith gave herself fully to the process. She understood that to represent these cultures authentically, she couldn’t just copy the surface. She had to study, to listen, to honor.

Her prints are still striking today because of how much dignity she gave to her subjects. In an era when many Western artists exoticized Asia for their audiences back home, Keith resisted caricature. Her Korean villagers, Japanese women in kimonos, Chinese landscapes, and Philippine scenes were not reduced to stereotypes. Instead, she portrayed them as they were—human, complex, vibrant, rooted in everyday life. That sensitivity set her apart. She wasn’t merely documenting; she was translating feeling into image.

Her career grew as her travels continued. She exhibited her prints in Tokyo, London, and across the United States, and her works found a place in major collections, from the British Museum to the National Gallery of Canada. Viewers responded to her honesty, the quiet poetry of her lines, and the way she balanced shadow and light. She was not just an outsider looking in—she was someone who tried to bridge two worlds.

Her artistry also extended into writing. In 1928, she published Eastern Windows, a book filled with observations and art from her journeys. Later, with her sister, she co-wrote Old Korea: The Land of the Morning Calm in 1946, blending description, history, and illustration. In her words, as in her prints, you can sense a longing to capture the fleeting, to make sure that traditions, faces, and stories would not be lost to time.

By the time she returned to London permanently, her life had been permanently reshaped by the East. She lived quietly until her death in 1956, leaving behind a body of work that still speaks across cultures. Looking at her prints today, there is a sense of stillness in them, as if she had indeed mastered the shadows—the play between what is seen and what is hidden, between presence and absence, between cultures separated by oceans yet connected in spirit.

Elizabeth Keith’s story is more than the tale of an artist abroad. It is about curiosity, respect, and the willingness to let another culture change you. It is about how art can serve as a bridge, and how one woman, with open eyes and steady hands, turned her travels into a lasting dialogue between worlds.

Daniel Reed is a curious mind with a passion for breaking down how the world works. With a background in mechanical engineering and digital media, he turns complex ideas into easy-to-understand articles that entertain and inform. From vintage tools and modern tech to viral internet debates and life hacks, Daniel is always on the hunt for the “why” behind the everyday. His goal is simple: make learning feel like scrolling through your favorite feed — addictive, surprising, and fun.