Barry Marshall Was Convinced That the Bacterium Helicobacter pylori Caused Stomach Ulcers, but No One Believed Him—So He Drank It Himself

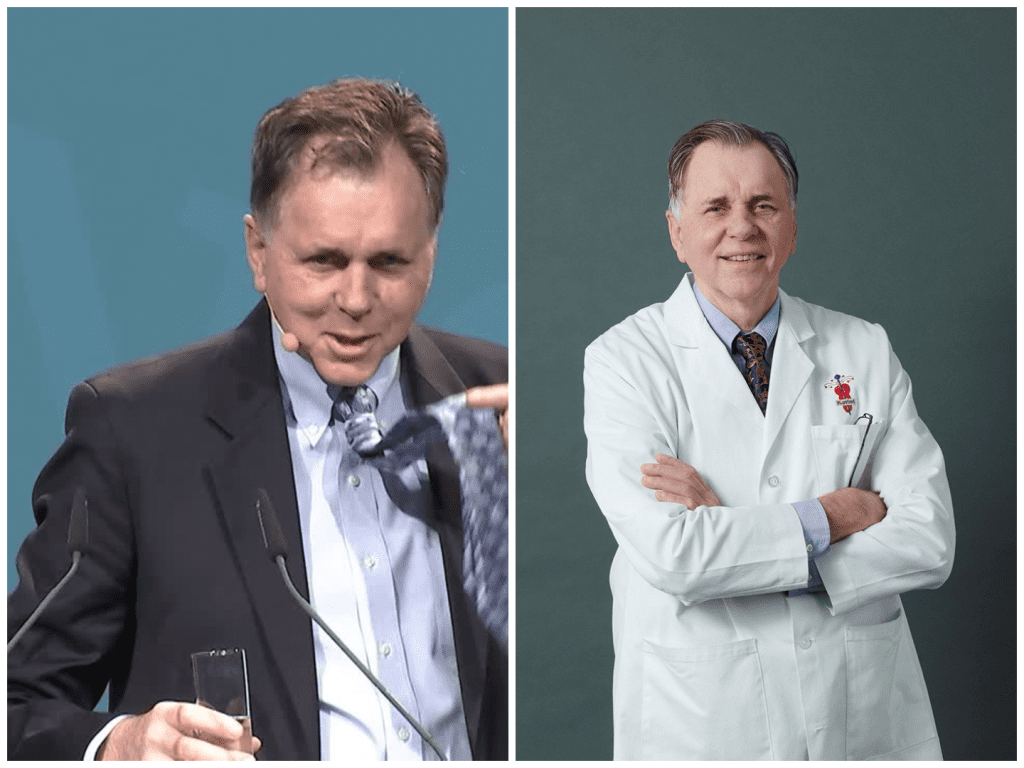

Barry Marshall’s story isn’t just about science—it’s about courage, stubbornness, and proving the world wrong in the most dramatic of ways. In the early 1980s, most doctors believed peptic ulcers were caused by stress, acid, or spicy food. But Marshall had a different idea. Along with pathologist Robin Warren, he suspected that a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori might be the real culprit behind gastritis and ulcers. Few believed them. And in a moment of audacious conviction, Marshall decided to drink a culture of the bacteria himself—to prove they were right.

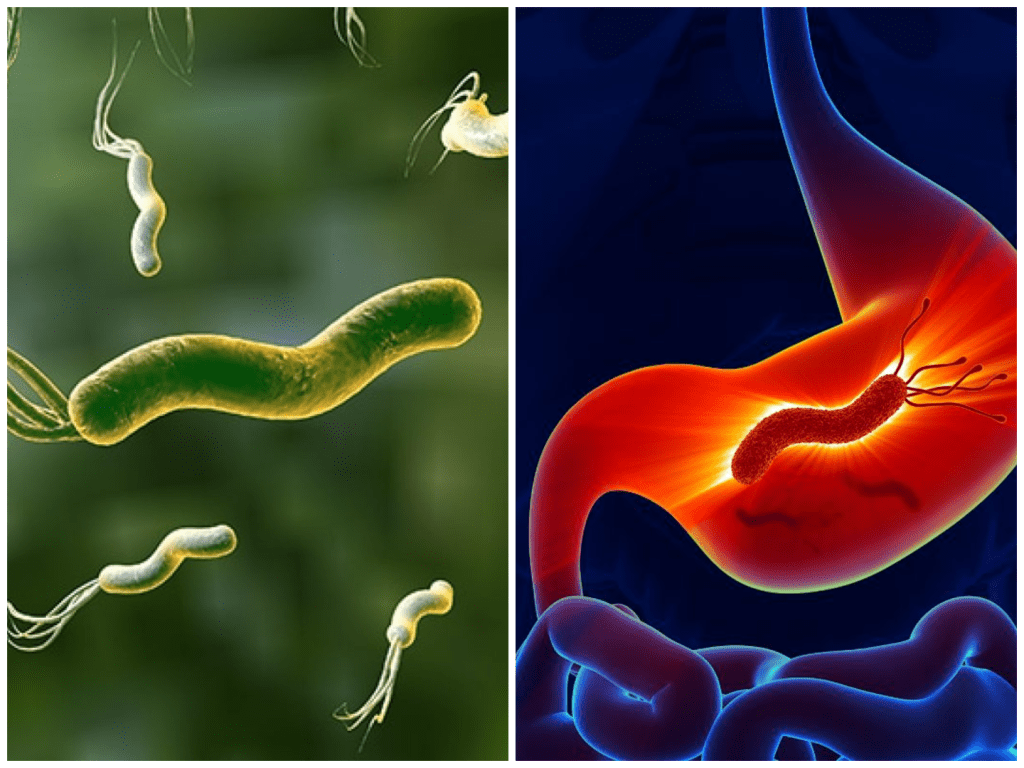

Marshall and Warren first noticed something odd in 1983 when they examined stomach biopsies under a microscope. They consistently saw a spiral bacterium in patients suffering from gastritis and ulcers. At the time, the medical community couldn’t accept that a bacterium could survive the harsh stomach environment. Yet Marshall and Warren persisted, publishing their findings in The Lancet in 1983 and 1984 saying H. pylori was linked to these conditions.

Despite years of lab work, no one could cultivate the organism in an animal model. Licensing bodies wouldn’t approve studies on humans. So Marshall did the only thing left: he took a risky step and drank the bacterial culture himself. Just days later, he fell ill with gastritis—nausea, inflammation, bad breath—the same symptoms his patients experienced. An endoscopy confirmed the bacteria were present in his stomach, and when he cured himself with antibiotics, it proved beyond doubt that H. pylori was responsible.

That act of self-experimentation was both thrilling and terrifying. While he risked his own health, he succeeded in completing Koch’s postulates—proving that the bacterium caused disease, not merely lived in the stomach. His bravery effectively shattered decades of medical orthodoxy.

The transformation in ulcer treatment was immediate. No longer did patients need lifelong acid reducers or surgery. Antibiotics became the new cure. Peptic ulcer disease shifted from being a chronic condition to one that was curable, accessible, and manageable. In some countries, like Japan, antibiotic treatments are credited with reducing rates of gastric cancer linked to H. pylori by nearly eliminating infections.

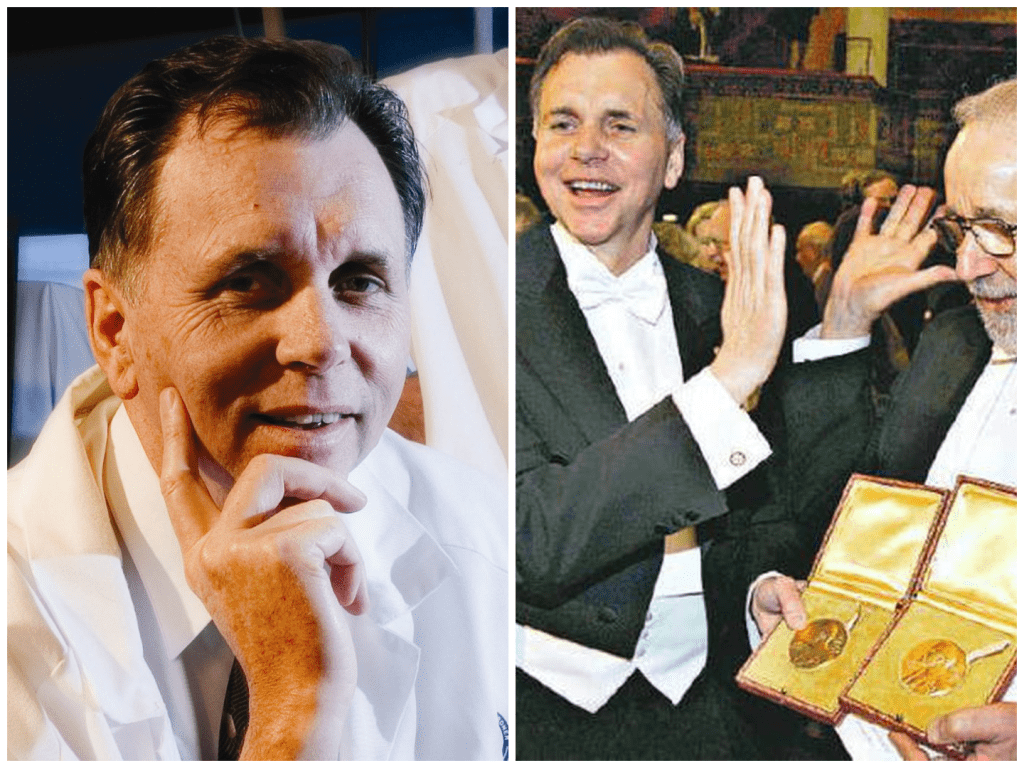

In 2005, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Barry Marshall and Robin Warren “for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.” It was a joyful vindication of years of ridicule and skepticism. The Nobel Committee praised their discovery for turning ulcer disease into a curable bacterial condition.

Marshall’s journey, however, didn’t end there. He earned awards like the Lasker Award (1995), the Gairdner International Award (1996), and was named Companion of the Order of Australia in 2007. He became co-director of the Marshall Centre and led ongoing research into H. pylori’s influence on other gut diseases. To this day, over half the world may carry H. pylori—infections that increase risk for gastric cancer. But thanks to Marshall, we know it can be treated.

Marshall’s story is a reminder that scientific progress isn’t always made in labs; sometimes it’s made in moments of personal sacrifice. He once said his wife was terrified as he drank that bacterial broth, but he insisted it was the only way to prove his theory. His work stands in a legacy of self-experimenters—courageous doctors who risked their own lives to push medicine forward.

Ulcer medicine today looks very different thanks to his defiant action. For patients, that means healing—real healing. No more surgeries or endless prescriptions, but a course of antibiotics can put ulcers to rest. That’s a gift born of courage, empathy, and a refusal to accept the unacceptable.

When we say “thank you” to Barry Marshall, we also honor the kind of bravery that transforms modern medicine. He didn’t just cure himself; he cured millions of others. That’s a legacy worth remembering.

Daniel Reed is a curious mind with a passion for breaking down how the world works. With a background in mechanical engineering and digital media, he turns complex ideas into easy-to-understand articles that entertain and inform. From vintage tools and modern tech to viral internet debates and life hacks, Daniel is always on the hunt for the “why” behind the everyday. His goal is simple: make learning feel like scrolling through your favorite feed — addictive, surprising, and fun.