China Just Built a 0.6 cm Spy Drone That Flies Like a Bug, Records Like a Camera, and Vanishes Like a Ghost

At first glance, you’d think it was just a mosquito. A tiny thing. A blur. A flicker near your ear. The kind of annoyance you’d swat at without even looking. But what if that mosquito wasn’t a bug at all? What if it was watching you, recording your voice, snapping photos — and then silently flying away, undetected?

That’s not science fiction anymore. That’s real. And it’s here.

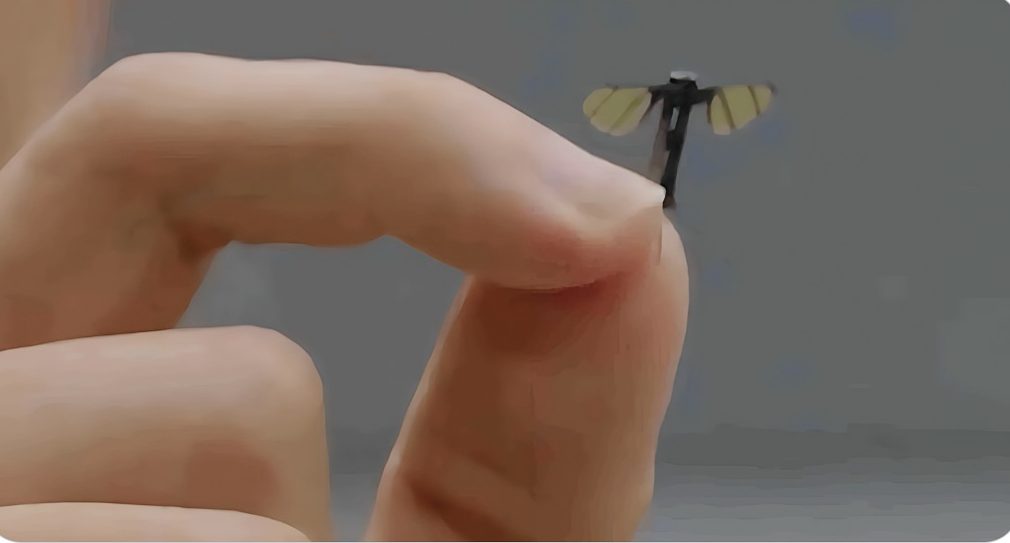

China has just unveiled one of the tiniest flying spy machines the world has ever seen. It’s called a micro-drone, but calling it that almost feels too plain. This thing is the size of a sesame seed — just 0.6 centimeters — and it’s been designed to look and move like a mosquito. It doesn’t buzz like a typical drone. It doesn’t spin with little rotors. It flaps its wings. It mimics real insect flight. And that alone is both stunning and terrifying.

Developed by researchers at the National University of Defense Technology (NUDT), the drone isn’t just about size. It’s about stealth. It’s built for military-level surveillance — the kind that slips through cracks, flies indoors, perches on windowsills, and listens from inside the room. It carries tiny cameras, microphones, and possibly even signal-collection tools. Think of it like a flying eye and ear that almost no one would ever notice — not even experienced security teams.

And here’s the craziest part: it’s practically invisible to radar.

This is where nature meets engineering. The drone uses biomimicry — a strategy where human technology copies the way living organisms work. In this case, it’s trying to fly like a real insect, especially a mosquito. That means it doesn’t make the usual mechanical noise you’d expect. It moves in a pattern so similar to nature that it blends in with the real thing. You’re not just dealing with advanced machinery. You’re dealing with camouflage that works on every level — visual, audible, and digital.

So what does this mean for the world?

Let’s talk about it.

Spying, Technology, and the Questions No One Wants to Ask

The potential behind this kind of drone is both fascinating and unsettling.

On the military side, the uses are obvious. This micro-drone could enter buildings without windows, slip past traditional security systems, and record everything without anyone ever knowing. It’s small enough to go unnoticed even in tight surveillance zones. Imagine a drone so small it could fly under a door gap, hover on a bookshelf, or follow a person without being seen. That’s not just futuristic — that’s now.

And it’s not just about war. Imagine this tech being used in international espionage, border surveillance, or political monitoring. A drone this tiny could gather information in ways that were once thought impossible without sending in actual spies. Now, it’s just a matter of programming and flying it in.

Some say it’s brilliant — a breakthrough in modern surveillance. Others say it’s dangerous. And both are probably right.

As soon as images and details of the mosquito drone hit social media, people had opinions.

“It’s cool until you realize it could be sitting on your plant right now,” one tweet read.

Another said, “We really are living in a Black Mirror episode.”

Many people joked nervously about swatting at flies just in case they were “bugged.” But underneath the jokes, the unease is real. Because what happens when this kind of tech becomes accessible beyond the military? What happens if it leaks? Or worse — what if it’s used against citizens, journalists, or everyday people?

Technologists are already raising ethical questions. How do we defend against something we can’t see? How do laws handle surveillance this small? If someone uses a mosquito drone to spy inside your home, how would you even know it was there? And who’s responsible if it ends up in the wrong hands?

These are the things no one wants to think about — but probably should.

But let’s not forget the other side. In the hands of rescue teams or disaster response units, this same drone could enter collapsed buildings, search for survivors in tight spaces, or carry sensors into radioactive or dangerous zones. It could be used in science, archaeology, or environmental work. It could help more than it hurts — if guided by the right hands.

Technology itself isn’t evil. It’s just a tool. But this tool, more than most, has the power to slip right past the boundaries of safety and privacy.

And it already has wings.

Daniel Reed is a curious mind with a passion for breaking down how the world works. With a background in mechanical engineering and digital media, he turns complex ideas into easy-to-understand articles that entertain and inform. From vintage tools and modern tech to viral internet debates and life hacks, Daniel is always on the hunt for the “why” behind the everyday. His goal is simple: make learning feel like scrolling through your favorite feed — addictive, surprising, and fun.